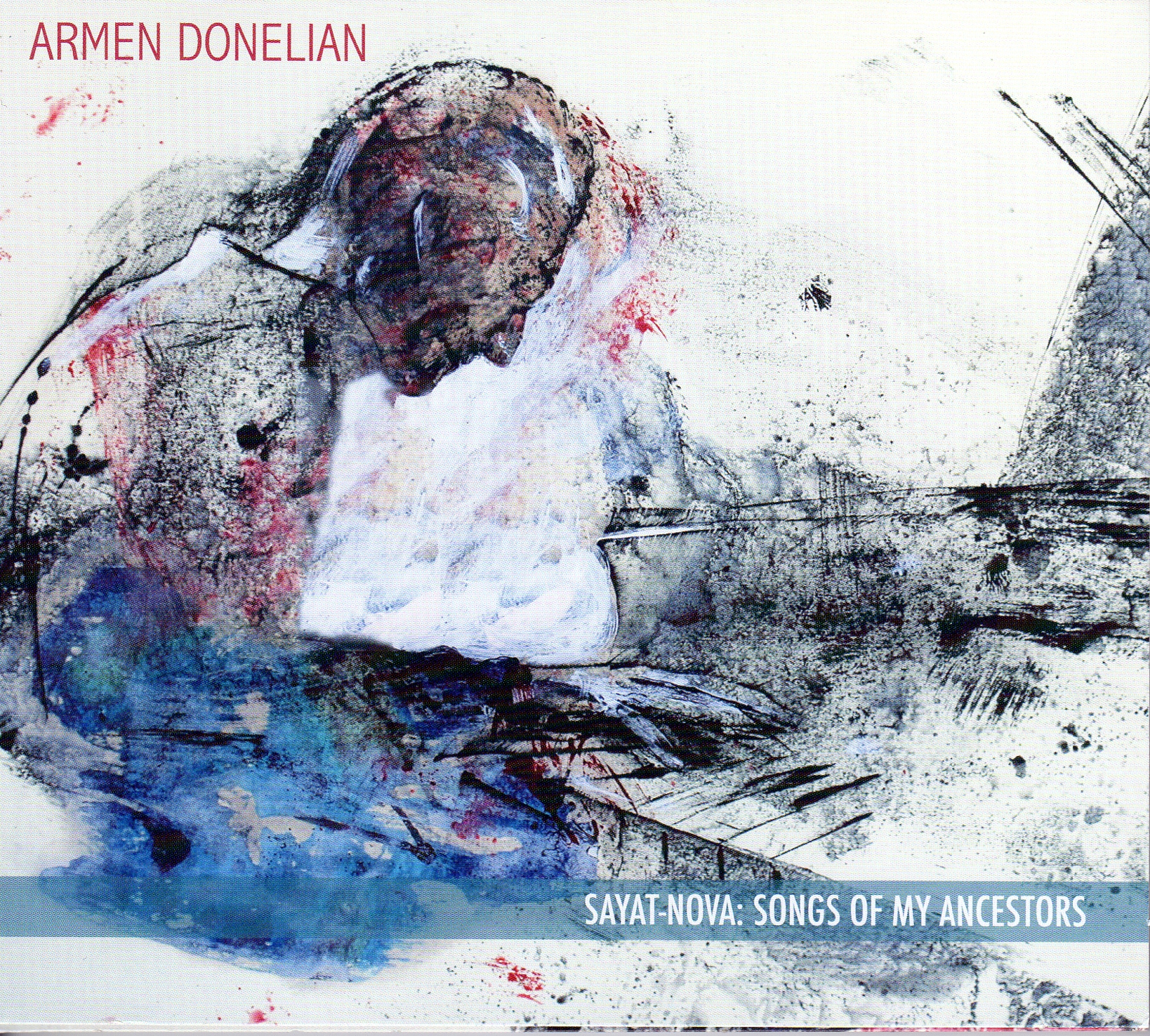

North Chatham Free Library presents ARMEN DONELIAN: SONGS OF MY ANCESTORS (solo piano)

"There are countless exquisite moments to be found within these extended meditations." - Downbeat

"Donelian's sense of touch and control is astonishing. His melodies emerge from the keyboard as if magically summoned, and his harmonies and multiple reharmonizations are full of profound depth and insight."

- Jazz Improv

Pianist/Composer Armen Donelian

ARMEN DONELIAN:

SONGS OF MY ANCESTORS

(solo piano)

Music of 18th-century Armenian troubadour Sayat-Nova interpreted by a contemporary jazz master

APRIL 24th, 3:00PM

Literature and the Arts Series

North Chatham Free Library

@ Uel Wade Studio

40 Church Street

Chatham, NY 12037

Free Admission

Info: (518) 766-3211

SAYAT-NOVA (1712-1795)

The young Sayat-Nova (his given name was Harutiun) was familiar with textiles, since his poems are filled with detailed cloth metaphors. He could have learned this trade as a practical skill to make a living although his poetic disdain for traders doesn’t extend to artisans.

Much of Sayat-Nova’s life is obscure. Even his face is a mystery, as his image does not exist. Twenty-eight years after his death (in 1823), Ioane, his youngest son, chronicled his father’s biography. It and Sayat-Nova’s poems provide the only clues to his life.

His father, Karapet (or Garabed), originated in Aleppo, Syria. His mother, Sara, came from Havlabar, a quarter of Tblisi, Georgia where a mixed Georgian & Armenian population lived.

Sayat-Nova was born in Sanahin, a small village in northern Armenia. Although he claimed Tblisi as his motherland, this is in a cultural or figurative sense only. He probably received a Church education since he was literate in both Armenian and Georgian. He was attuned to Islamic and Christian themes, and from the mixture of his texts he reveals a split cultural personality, a psychological composite.

By the time he was 18 (1730), he had become a troubadour, most likely through his own self-taught efforts, devoted to playing the kamanche, the chongur and the tar (or tambure) and to proclaiming his love through minstrelsy. Later in life, though, he complains in a song, “This minstrelsy has brought me much sorrow.”

At 30 (1742), Sayat-Nova joined the retinue of the royal court of Georgia as an indentured serf. He may have answered directly to King Irakli II or, more likely, one of his two sons (24 years younger than Sayat-Nova). Irakli was an intelligent, handsome and sensitive man with a melodious voice. He inspired Sayat-Nova’s allegiance, perhaps due to his ancient Armenian roots. While the artist and the noble both had a claim to greatness, yet, the two were compelled by birth to remain at arm’s length. Sayat-Nova resented the material affluence purchased by his royal servitude, though he did develop his poetical and musical talents as a result of it.

While it’s unlikely he was the chief court minstrel, but rather one among several, Sayat- Nova was undeniably the outstanding troubadour of his time and place, a poet of the first order writing and singing in Armenian, Georgian, Azeri, Persian, Turkish and even flawed Russian. Some poems were also transliterated between languages.

At 41 (1753), in Ode, one of his most celebrated verses, Sayat-Nova narrates in both mystical and majestic terms how he may have been unjustly slandered and persecuted for imagined wrongs, and with pride in his poetic and musical gifts he appeals to the King for justice. He admits his powerlessness before the King who, if swayed by calumniators, could banish him from the country. “Do not cause Sayat-Nova’s tomb to be an Indian, Abyssinian or Arabian one,” he prays, always faithful to his Armenian lineage.

Ironically, at 47 (1759), at the height of his faculties, Sayat-Nova was, in fact, dismissed from the royal court, after which he never played or sang publicly again. He took sacred vows and served as a married parish priest in an Armenian church in the remote trading post of Anzal on the southern shore of the Caspian Sea (now in Iran). It’s not clear how long he was there, but by 1765 – after copying several ancient and lengthy manuscripts and writing down his poems in a volume titled Tetrak (now in the Museum for Literature in Yerevan, Armenia and signed “Stepanos,” his religious name) – Sayat-Nova, now 53, returned to Zakatali, east of Tblisi.

Sayat-Nova had three, maybe four, children within a roughly ten-year period (1758-68), including three sons – Melikset, the father of Movses (1810-1883), Grigor and Ioane (who wrote his father’s above-mentioned biography). After his wife Marmar died in 1768, Sayat-Nova became a (probably reluctant, though compliant) monk in Haghpat monastery, just a few meters east of his birthplace of Sanahin. Both districts were prosperous possessions of the royal rulers of Georgia, and so the court may have facilitated Sayat-Nova’s transition to Haghpat where he would have lived a relatively comfortable life. Sayat-Nova remained there until his death at 83 during the siege of the city by the raiders of the Persian tyrant Agha Muhammad Khan Kajar.

This much is fairly certain. - AD